Cetacean backbone ecomorphology

Ecomorphology and biomechanics of cetacean backbone in an evolutionary context

Cetaceans (whales, dolphins, and porpoises) represent the most speciose taxon of extant marine mammals and exhibit a tremendous ecological disparity. Although all cetaceans possess a streamlined and hydrodynamic body adapted to their aquatic environment, they also have a wide phenotypic variability at the level of body size, body shape and fin shape. Moreover, the different species exhibit extraordinary disparity in the shape of their vertebral column. As whales and dolphins swim with dorso-ventral oscillations of their backbone, modifications of their vertebral morphology should impact their ability to swim in different kinds of habitats. However, relationships between the vertebral morphology, swimming performances, ecology, and evolutionary history of cetaceans remain uncertain.

My PhD aimed at providing concrete elements regarding the causes and consequences of the large morphological variability of the cetacean backbone. To this purpose, we computed the largest database of cetacean vertebral morphology ever created by quantifying the vertebral shape of 73 species (i.e., 80 % of extant diversity). These morphological data were combined to backbone biomechanics and swimming kinematics data and were analysed in both evolutionary and ecological contexts.

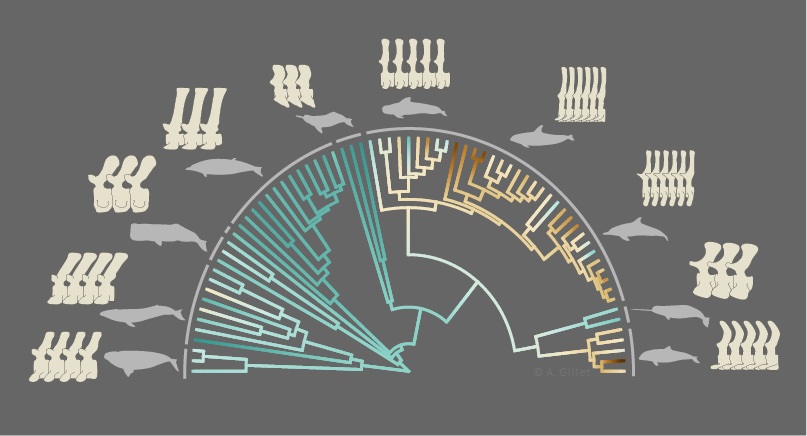

The results demonstrate that both ecological and phylogenetic factors are associated to vertebral shape. We identified two distinct phenotypic evolutionary patterns: non-delphinoids and delphinoids.

Non-delphinoids are a paraphyletic group comprising several cetacean clades: mysticetes, sperm whales, beaked whales, and ‘river dolphins’. They are all characterised by a low number of elongated vertebrae, resulting in relatively flexible backbones. In this clade, inshore species retained a small body size while offshore species evolved towards an increased body size accompanied by a slightly increased vertebral count (pleomerism). The small size of riverine species ensures manoeuvrability in complex environments while gigantism of offshore species provides adaptation to deep diving, long distance migrations, and bulk-feeding.

Delphinoids form a monophyletic group comprising three families: Monodontidae (narwhals and belugas), Phocoenidae (porpoises) and Delphinidae (oceanic dolphins), the most species-rich cetacean family. They all possess an extremely modified vertebral morphology, unique among mammals, by having an extraordinary high number of disk-shaped vertebrae while retaining a small body size. In this clade, inshore species have a lower vertebral count than offshore species. Within delphinoids, the closely related porpoises (Phocoenidae) and oceanic dolphins (Delphinidae) have clearly distinct vertebral morphology and follow slightly different phenotypic trajectories along the habitat gradient, probably reflecting parallel evolution with similar responses to same constraints. Furthermore, similar morphological adaptations are found between coastal and offshore ecotypes in the common bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops truncatus) suggesting that similar constraints act both at the micro- and macroevolutionary levels. The extreme vertebral count increase and associated vertebral shortening observed in offshore delphinoids increases the stiffness of their backbone.

These modifications provide enhanced body stability and allow delphinoids to use higher tailbeat frequencies in an energetic efficient manner, resulting in higher swimming speed.

These new functional abilities allowed small delphinoids to exploit scattered oceanic resources in a new way and can be considered as key innovations that supported their explosive radiation and ecological success.